ptr_to_unique<T>, extending std::unique_ptr to support weak secondary smart pointers

5.00/5 (8 votes)

A smart pointer to an object already owned by a unique_ptr. It doesn't own the object but it self zeroes when the object is deleted so that it can never dangle.

- Download ptr_to_unique.zip - 3.3 KB

- Download VS 2019 demo project - 50.3 KB

- Download Windows demo executable - 62.6 KB

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Design

- notifying_unique_ptr

- ptr_to_unique

- make_notifying_unique function

- Using Your Own Custom Deleter

- Safety and Performance

- Runtime Error Handling

- Using the Code

- Top Dog Demo App

- The Implementation Code

- Summary

- Why doesn't unique_ptr already have a smart weak companion like shared_ptr?

- History

Introduction

The Standard Library provides three smart pointers, one for single ownership and two for shared ownership:

| ownership | owning | non-owning | ||||

| single | unique_ptr<T> | nothing here | ||||

| shared | shared_ptr<T> | <-- | weak_ptr<T> |

I think there should be four. There is clearly one missing.

Why is there no non owning smart pointer to point at something already owned by unique_ptr with the smart property that it self zeroes if its pointee is deleted?

I can't answer that question and that troubles me, but I can say two things:

- It is needed and the lack of it has probably for many years been a major cause of project wrecking dangling pointers and the reputational damage they have done to the language.

- It can be done and I present a working implementation here.

Background

It is generallly recommended that any further references to an object owned by unique_ptr should be held as a raw pointer because it has the required property that it doesn't own the object. That is true, but being just a raw pointer, it has the inconvenience that it continues to point at where the object used to be after it has been deleted – it is left dangling. The intuition that the pointer might self-zero when its pointee is deleted is wrong. For that to happen, it needs to be smart.

Consider the following drawing code which has a simple optimisation to avoid having to call the lengthy FindObjectOfInterest function (which returns a reference to a unique_ptr) each time the screen is updated.

object* g_pObjectOfInterest = NULL;

std::vector<unique_ptr<object>> collection;

void DrawObjectOfInterest()

{

if(NULL==g_pObjectOfInterest)

g_pObjectOfInterest = FindObjectOfInterest(collection).get();

g_pObjectOfInterest->Draw()

}

On the surface, it looks well designed but what happens if the object gets deleted? Well, the null test won't catch it because g_pObjectOfInterest still points at where the object used to be so Draw() will be called on a dangling pointer.

Don't think that this danger has stopped programmers from writing code like this. It solves a problem and it is a problem that must be solved. Therefore it is done. If the danger is recognised, then some attempt will have been made to mitigate it, but this is a place where a lot of mistakes get made. As there is no test, you can do to see if a non-zero raw pointer is still valid, mitigation is about writing code to reset pointers and making sure that it gets called when objects get deleted. With no particular strategy recommended for this, these mitigations tend to be ad hoc spaghetti code and even if comprehensive can be very fragile.

I am sure I am not the only programmer working in a single ownership context (most code) who has looked longingly at shared_ptr with its non-owning weak_ptr partner. It is tempting to impose shared ownership on even fundamentally single ownership designs just to have that non-owning weak_ptr which 'knows' when its pointee has been deleted. Like this:

weak_ptr<object> g_wpObjectOfInterest = NULL;

std::vector<shared_ptr<object>> collection;

void DrawObjectOfInterest()

{

shared_ptr<object> spT(g_wpObjectOfInterest);

if(NULL==spT)

{

spT = FindObjectOfInterest(collection).get();

g_wpObjectOfInterest = spT;

}

spT->Draw();

}

weak_ptr has the added inconvenience of having to convert it to a shared_ptr every time you want to do anything with it but the main problem is you no longer have unique ownership and that can matter a lot. In this case, it could mean that an object is removed from the collection but lives on because a shared_ptr somewhere still references it. Being no longer in the collection, it would no longer appear in any enumerations (effectively invisible) but some things might still reference it and may still act on it. That is the kind of mess that can be difficult to detect and sort out.

We should not have to be looking to shared ownership just to get a smart non-owning pointer and keep our pointers from dangling. We should have a smart non-owning pointer that works with unique_ptr and there is no reason why we can´t. It can´t be zero overhead but it can be just the overhead needed for the job and it is a job that needs to be done.

Design

We want a smart pointer, we'll call it ptr_to_unique, that can be initialised from a unique_ptr, has no ownership of the object and therefore never deletes it and is guaranteed to read as null if its pointee gets deleted. The tricky part is the last one. It has to start with; How will our smart pointer even know when the object gets deleted?

Fortunately, unique_ptr allows for custom deleters which get called whenever the object gets deleted. So we can define a custom deleter that notifies our smart pointer of any deletions. We don't want our custom deleter to actually do the deletion. It can leave that to std::default_delete or allow a real custom deleter to be passed through.

It is fortunate that unique_ptr provides for a custom deleter and it is entirely conformant to exploit it in this way. The fundamental design decision was to accept this and harness the opportunity.

So ptr_to_unique requires a modification to the definition of the unique_ptr it is going to reference:

std::unique_ptr<T>

must be changed to:

std::unique_ptr<T, notify_ptrs<T>>

a using declaration allows this to be written more concisely as:

notifying_unique_ptr<T>

This also makes the required edit quite simple:

/*from*/ std::unique_ptr<T>

/*to*/ notifying_unique_ptr<T>

Although it is logical to use the notifying_unique_ptr form (and I will do so throughout this article)

there may be strong cultural reasons for not doing so. notifying_unique_ptr might appear to be a supplanter or imposter of unique_ptr and cause consternation in code reviews. Whereas with...

std::unique_ptr<T, notify_ptrs<T>>

...it is more transparent that you are using an authentic std::unique_ptr and complementing it with a deleter hook that performs notifications.

The usage can be illustrated by recoding the drawing code described above:

ptr_to_unique<object> g_puObjectOfInterest;

std::vector<notifying_unique_ptr<object>> collection;

void DrawObjectOfInterest()

{

if( ! g_puObjectOfInterest)

g_puObjectOfInterest = FindObjectOfInterest(collection);

g_puObjectOfInterest->Draw();

}

This code is safe requiring no extra code to be written because g_puObjectOfInterest is a ptr_to_unique and will read as null if the object has been deleted causing it to be re-initialised from FindObjectOfInterest() before calling Draw() on it, as the design intended.

The implementation uses a hidden reference counted control block similar to that of shared_ptr/weak_ptr but lighter and not burdened with thread safety mechanisms. The thread safe sharing of references across threads supported by shared_ptr/weak_ptr is not a possibility with the exclusive ownership of unique_ptr.

notifying_unique_ptr

notifying_unique_ptr<T, D> is not a thing in itself. It is no more than shorthand for:

std::unique_ptr <T, notify_ptrs<T, D>>;

It is the notify_ptrs deleter that enables std::unique_ptr for use with ptr_to_unique. The only changes this makes to the unique_ptr are:

- It passively intercepts deletions to send notifications.

- It stores an extra pointer to where the notifications need to be sent.

The extra storage means that it is no longer zero overhead, as a plain unique_ptr would be. So the 'upgrade' should only be made when needed. Where it is needed, it is a small price well worth paying.

Transfer of Ownership

The notify_ptrs deleter doesn't change how the object is deleted and that is reflected in transfer of ownership. Transfer from a plain unique_ptr<T, D> to a notifying_unique_ptr<T, D> is allowed:

std::unique_ptr<T> apT1 = std::make_unique<T>();

notifying_unique_ptr<T> apT2 = std::move(apT);

//also implicit in

notifying_unique_ptr<T> apT2 = std::make_unique<T>();

as is transfer from a notifying_unique_ptr<T, D> to a plain unique_ptr<T, D>:

apT1 = std::move(apT2); //any ptr_to_uniques referencing apT2 will be zeroed

The latter will cause any ptr_to_uniques that the notifying_unique_ptr may have accrued to be zeroed because the new ownership has no notification mechanism to keep them informed of deletions.

Transfer between one notifying_unique_ptr and another does not zero any ptr_to_uniques. They will continue to reference the same object. If you do not want this, for instance, when passing it to be worked on by another thread. A free function is defined to act on notifying_unique_ptr to allow this:

zero_ptrs_to(a_notifying_unique_ptr);

It returns a reference to the notifying_unique_ptr so it can be conveniently inserted in a call to std::move or std::swap:

notifying_unique_ptr<T> apDest = std::move(zero_ptrs_to(apSrc));

ptr_to_unique

The code written using ptr_to_unique will look very much like that you would have otherwise written for a raw pointer. Very little editing is required to convert existing code. There are some important differences though:

The declaration is different and ensures that it initialises to nullptr or to point at a valid object.

ptr_to_unique<T> puT; //automatically intialises to nullptr

ptr_to_unique<T> puT(nullptr); //explicitly intialises to nullptr

ptr_to_unique<T> puT(a_notifying_unique_ptr); //will be a valid object or nullptr

ptr_to_unique<T> puT(another_ptr_to_unique); //will be a valid object or nullptr

Assignments are as they would be for a raw pointer referencing a unique_ptr but not requiring calls to .get():

ptr_to_unique<T> puT = nullptr; //will be nullptr

ptr_to_unique<T> puT = a_notifying_unique_ptr; //will be a valid object or nullptr

ptr_to_unique<T> puT = another_ptr_to_unique; //will be a valid object or nullptr

but it will not allow the following incorrect assignments to compile:

ptr_to_unique<T> puT= some_raw_pointer; //error, source not owned by a unique_ptr

notifying_ unique_ptr<T> apT = a_ptr_to_unique; //error, non-owner cannot initialise owner

ptr_to_unique<T> puT= make_unique<T>(); //error, ptr_to_unique cannot take ownership

The clarification of owner and non-owner types generates an extra set of grammatical rules that the compiler enforces. This helps to keep code clear and coherent.

The boolean and dereference operators also operate as they would for a raw pointer:

if(pT)

pT → do_something();

Equality comparison can be used with a notifying_unique_ptr a raw pointer or another ptr_to_unique.

if(puT == pT)

puT → do_something();

if(puT != pT)

puT → do_something_else();

Pointer arithmetical comparisons (> and <) are not supported nor are any other pointer arithmetical operations (++, –, + etc.) .

ptr_to_unique can be declared as a const and set to point at a valid object on initialisation but it will still self zero if that object is deleted. Otherwise, it behaves as const – you can never point it anywhere else:

const ptr_to_unique<T> puT = a_notifying_unique_ptr; //exclusively for tracking this

//while it lives.

ptr_to_unique provides a get() dot method which returns a raw pointer to the object being referenced:

T* pT = puT.get();

You will need this when passing the object being referenced into a function that takes a raw pointer.

While casting from base to derived class is dangerous, it is sometimes impossible to avoid. To enable this, ptr_to_unique supports a dot method:

ptr_to_unique<Derived> puDerived = puT.static_pointer_cast<Derived>();

make_notifying_unique function

You can initialise a notifying_unique_ptr with std::make_unique because notifying_unique_ptr can take ownership from a plain unique_ptr,

notifying_unique_ptr<my_class> apClassObj = std::make_unique<my_class>(parm1, parm2, …);

However if you try to use auto to avoid verbosity and repetition

auto apClassObj = std::make_unique<my_class>(parm1, parm2, …);

then what you will get is a plain unique_ptr that won't support ptr_to_unique.

Instead you can use make_notifying_unique

auto apClassObj = make_notifying_unique<my_class>(parm1, parm2, …);

This way you are more explicitly asking for what you want and that is what you will get. A notifying_unique_ptr<my_class> that will support ptr_to_unique

make_notifying_unique has one more trick up its sleeve which is revealed in the next section.

Using Your Own Custom Deleter

To provide your own custom deleter for notifying_unique_ptr, simply pass it as the second template parameter as you would with unique_ptr:

xnr::notifying_unique_ptr<T, MyDeleter<T>> apT;

or if you use the uncontracted form, pass it as the second template parameter to notify_ptrs:

std::unique_ptr<T, notify_ptrs<T, MyDeleter<T>> apT;

Unlike std::make_unique, you can use make_notifying_unique with a custom deleter but it must implement a static allocate method with the following signature:

template <class... Types>

static inline T* allocate(Types&&... _Args)

It must be static because it will be called in a void before anything gets constructed. Here is an example of a compliant allocating deleter that simply replicates the defaults.

template <class T>

struct an_allocating_deleter

{

//required by std::unique_ptr

void operator()(T* p)

{

//replace with your deletion code

delete p;

}

//required by make_notifying_unique

template <class... Types>

static inline T* allocate(Types&&... _Args)

{

//replace with your allocation code

return new T(std::forward<Types>(_Args)...);

}

};

The allocating deleter is a good way to encapsulate and centralise your matching allocation and deletion code and ensure that their application doesn't get wires crossed.

You can create a notifying_unique_ptr with such a deleter as follows

auto apClassObj =

make_notifying_unique<my_class, an_allocating_deleter<my_class>>(parm1, parm2, …);

You can also initialise a plain zero overhead unique_ptr with make_notifying_unique and pass in a custom allocating deleter to enjoy the same benefits..

std::unique_ptr<my_class> apClassObj =

make_notifying_unique<my_class, an_allocating_deleter<my_class>>(parm1, parm2, …);

This is possible because ownership can be transferred from notifying_unique_ptr to std::unique_ptr.

Yes it looks wrong to initialise a plain unique_ptr with make_notifying_unique and half of the initialisation effort of the intermediate notifying_unique_ptr will get thown away. So to save blushes, a custom_make_unique function is also provided.

auto apClassObj = custom_make_unique<my_class, an_allocating_deleter<my_class>>(parm1, parm2, …);

apClassObj will be a plain std::unique_ptr correctly initialised with no intermediate notifying_unique_ptr.

If you need to access your deleter after construction, you will find that notifying_unique_ptrs get_deleter() method will return the notify_ptrs deleter, not the one you passed.

auto deleter = apClassObj.get_deleter();

//deleter will be a notify_ptrs

deleter.my_data = x; //error notify_ptrs doesn't have a my_data member

However the notify_ptrs deleter offers an implicit conversion to your passed in custom deleter. You just have to ask for it.

an_allocating_deleter<my_class> deleter = apClassObj.get_deleter();

//deleter will be an_allocating_deleter

deleter.my_data = x; //ok if your custom deleter has a my_data member

Safety and Performance

Inevitably, there is some trade off between safety and performance and ptr_to_unique prioritises safety. It will not dangle. It is designed to be above all a reliable infrastructure node that can safely be used in a fairly casual manner allowing you to design and build with it confidently.

Like shared_ptr, there is an overhead when a ptr_to_unique is initialised, including either allocating a control block or bumping a reference count. Unlike shared_ptr and unique_ptr, there is also an overhead on every dereference as it checks the control block for validity first.

Of course, if you have written your code correctly, you will have already checked its validity - making all those checks on dereference redundant. The problem is that only you know this and are you absolutely sure? Sometimes, you can be. You may be further discomforted by knowing that all you get for all this checking is that, should you make a mistake, your program will issue a defined error message and terminate instead of running on with a dangling pointer. If it happens, then you will be grateful for that critical distinction. A dangling pointer can do a lot of damage.

The dereference overhead is only a few instructions and will be negligible unless you are working ptr_to_unique very hard in a very atomic manner., e.g., using it to dereference class member variables individually and doing very little with them. In these cases, if you are sure you have checked the validity first and that it will stay valid while you work on it, you can simply extract the raw pointer into local scope (having checked its validity as a ptr_to_unique) and work with that instead.

ptr_to_unique<T> puT;

//some code that may or may not initialise puT

if(puT)

{

T* pT = puT.get(); // pT does no checking and has no protection against dangling

//some code that works pT very hard

//be sure not to call anything that might delete the object

}

I am sure that bare metal purists will do this habitually and that is fine as long as it is accompanied by the required due diligence to ensure it is being done safely. Tightly scoping the lifetime of the extracted raw pointer helps greatly with this.

For the most part, it is simpler and safer to work directly with the ptr_to_unique.

if(puT)

puT->DoSomthing();

Runtime error handling

ptr_to_unique will never give you a dangling pointer to run with but it can give you a null pointer. If you write code that deferences a null pointer then you have a runtime error - one that the compiler cannot know about and catch. Execution cannot proceed as intended and therefore you will want it to stop and flag what has happened. C++ provides exceptions for this, even allowing you to try/catch them and recover execution in a wider scope.

The scheme for ptr_to_unique is:

calling the → operator on a null pointer.

It returns the null pointer which will immediately provoke a null dereference exception in the user code, exactly where the bad dereference was made. This is the same as with unique_ptr.

calling the * operator on a null pointer.

It throws an immediate exception so you don't get as far as symbolising a null object. Stepping back through the call stack will take you directly to where the bad dereference was made This differs from unique_ptr which simply returns a null object and relies on an exception being thrown the first time you try to do anything with the null object you have succeeded in symbolising. This is less convenient but it is better than breaking the zero overhead of unique_ptr by impeding a dereference with a non zero test.

ptr_to_unique has to do a test on every dereference anyway so there is no further cost in throwing an exception when an error condition is clearly occurring.

They are designed to bring your attention as quickly as possible to the location of the error in your code.

Using the Code

First, include ptr_to_unique.h. The download link ptr_to_unique.zip is at the top of the page.

This will bring in <memory> from the standard library so it must exist in your include path.

Everything is defined within the namespace xonor. A shorter alias xnr is provided that is more convenient to code with, particularly if you have auto complete. So the declarations will be:

xnr::notifying_unique_ptr<T> apT;

//or in the unabbreviated form

std::unique_ptr<T, xnr::notify_ptrs<T>>

and:

xnr:: ptr_to_unique<T> puT = apT;

ptr_to_unique is not zero overhead and the notify_ptrs deleter adds storage to notifying_unique_ptr. For that reason, it should not be used as a canonical replacement for every pointer that references a unique_ptr. It is only required for pointers that are set and then retrieved later after other things have been allowed to happen.

The uses of ptr_to_unique can be remedial or innovative.

Let us look at remedial actions first.

The first step is to look for where you need to use ptr_to_unique. Start by looking for pointers that are class members or globals. Their persistence potentially exposes them to dangling.

Those that persist from one event handler to another are at very high risk because anything may have happened including the user deciding to close the application. Use ptr_to_unique for these.

Those that persist from one function call to another are also at risk although there will be many cases where careful examination can determine that there is no risk.

Finally, look for rare cases where a function body may accidentally delete the object it is working with. A classic is calling PeekMessage in the middle of some intensive processing to prevent the GUI from appearing frozen. The object you are working on may not be there after PeekMessage returns. If you use ptr_to_unique, you will at least be able to check if it is still there.

Once you have found which pointers need to be ptr_to_unique, you will then need to 'upgrade' the unique_ptr they reference to a notifying_unique_ptr.

Remember that you still have to test a ptr_to_unique for non-null when you pick it up to use. It doesn't guarantee that the pointer is valid – it isn't an owner. It guarantees that the non-null test is a reliable test of its validity.

Correct use of ptr_to_unique is strictly enforced during compilation. But of course, that won't protect you from run-time errors such as a null dereference - those will be caught at run-time.

Now for innovative use.

In real life, we hold direct references to each other (phone numbers, e-mail addresses, etc.) and we find this very useful. We can reference each other and we can pass references we have onto other people. Yet with software, we shy away from letting objects reference each other for fear of finding our pointers dangling. This fear limits our design and our imagination.

ptr_to_unique removes these limits. You can happily allow objects to reference each other and if one dies, then you will know because its reference (the ptr_to_unique) will read as null. You can also allow objects to pass on references that they hold to other objects. All ptr_to_unique references to an object will read as null if the object is deleted, regardless of how the ptr_to_unique was obtained. This freedom to fearlessly propagate references to volatile objects is exemplified in the demonstration application described below.

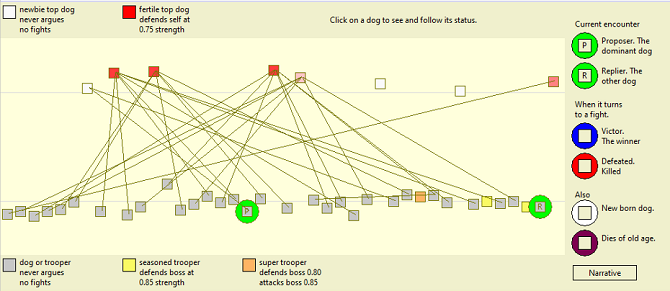

Top Dog - The Demonstration Application

Microsoft Visual Studio 2019 project for Windows. The download link Top_Dog.zip is at the top of the page. Or you can just download the Windows executable and run it Top_Dog_Exe.zip

The goal of this application is to set up a dynamic where ptr_to_unique references are constantly being taken, held, propagated and used while the objects that they reference are being constantly destroyed in an unpredictable manner. I wanted to demonstrate not just that ptr_to_unique is robust enough to take this kind of battering but also that using it in this way can be useful for modelling a plurality of objects that form relationships with each other. In order to give it a focus that makes some sense to work with, I decided to use the familiar Top Dog metaphor to hang it on.

The application models a collection of dogs who are willing to follow a strong boss but also have some desire to be a boss themselves. They encounter each other at random constantly resolving the issue of who is strongest and should be adopted as the boss and occasionally fighting to the death over it. They also weaken and die with old age and Top Dogs (a boss that has no boss) can be fertile and produce new dogs.

The collection of dogs is represented by a std::vector of notifying_unique_ptrs:

std::vector<xnr::notifying_unique_ptr<Dog>> dogs;

When dogs are born, they are added to the collection and when they die, they are removed.

The action is all about who each dog takes to be their boss and that is represented by each

dog holding a ptr_to_unique that points to their boss.

xnr::ptr_to_unique<Dog> puBoss;

puBoss can be null and it can become null so it is tested before use after any action has been allowed to happen. This is how you always use a ptr_to_unique.

One dog may be persuaded to adopt another dog as his boss:

puBoss = apOtherDog;

or adopt the other dog's boss as his boss:

puBoss = apOtherDog->puBoss;

This produces a dissemination of references to the stronger dogs that would be very difficult to track and manage without the use of ptr_to_unique.

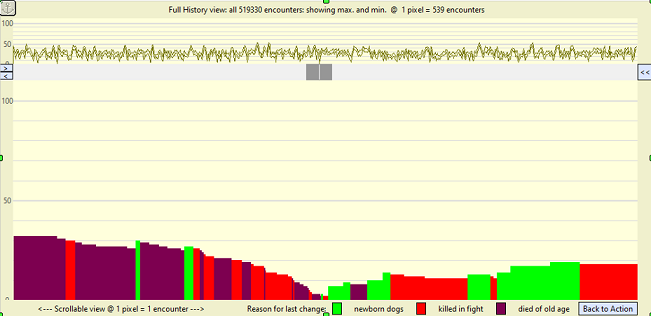

There is a bit of diversity to the rules of engagement to keep it interesting and it has been tuned, not to be realistic, but to produce a dynamic that is disruptive and unpredictable but sustainable enough to run for a while. This is illustrated graphically as it happens. I became curious about the way the dog population evolved so added the means to run the model at a much faster rate without display [Jump 500000] and an interactive history view to examine the result of many interactions.

It would be problematic to have used shared ownership so that weak_ptr can be used instead of ptr_to_unique because the death of a dog must be definitive and only unique ownership can properly encapsulate this. The model may be course and a poor match to reality but let us at least get it right that dead means dead.

It is just a spoof model contrived to show that ptr_to_unique can open up new ways of doing things but I have had a lot of fun with it and remain fascinated by some aspects of its behaviour.

I have released the demo app code untidied, warts and all, because it works and I wanted to get on with releasing ptr_to_unique.h which is carefully coded, tidied up and ready for use. I will be tidying up the demo app as I continue to mess about with it.

The Implementation Code

ptr_to_unique, like other smart pointers is intended to be placed in a library and usable almost as a language element. That means it must work correctly in any context and this requires a very high level of correctness in how it is coded. I invite anyone to examine ptr_to_unique.h to check that this has been achieved or otherwise. I have tried to present the code so that this is a reasonable task.

What follows is not a complete description. I hope the code largely speaks for itself, but I think it is helpful to give an overview of the architecture and to explain some of the not so obvious design decisions.

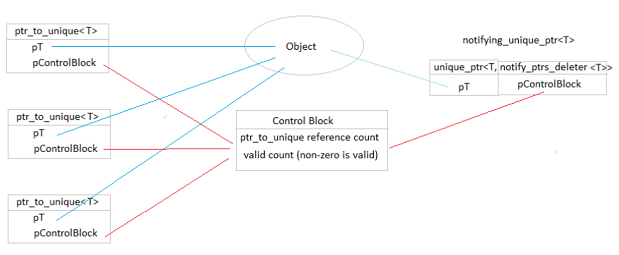

Each ptr_to_unique carries its own local pointer to the object but that pointer is only accessed once the valid count has been checked in the Control Block. If the valid count is zero, then the local pointer is ignored and the ptr_to_unique reads as null. When the object is deleted, the notify_ptrs deleter accesses the Control Block and sets the valid count to zero so that all ptr_to_uniques referencing it will now read as null.

The Control Block lives as long as anything is referencing it. The ptr_to_unique reference count keeps track of this. When ptr_to_unique reference count is zero and the valid count is zero, the Control Block will delete itself.

There is nothing revolutionary about the design. The only thing that is novel is deciding to do it in this context.

Division of Labour

ptr_to_unique and the notify_ptrs deleter are typed (templated) by the object they point at. So any code that doesn't get optimised away could potentially be instantiated multiple times. However, the Control Block and the pointers that reference it are not templated on the object type and therefore code using them should be instantiated once only. To ensure that the compiler sees this, the labour is divided between that which is templated on the object type (blue lines on the diagram) and that which is not (red lines on the diagram).

This is done by creating a wrapper for the pointer to the control block which encapsulates all operations involving the ControlBlock including testing if it exists and allocating it when required. This is called _ptr_to_unique_cbx (not templated) and its methods are the only access to the control block which is declared privately within it.

Any part of ptr_to_unique operation that does not depend on the object type is delegated to _ptr_to_unique_cbx.

The notify_ptrs deleter

The notify_ptrs deleter is a key component and also the most innovative. Its design is not obvious and requires some explanation.

The notify_ptrs deleter must implement operator()(T* p) , which unique_ptr will call to do the deletion, and use this to achieve its key functionality which is tentatively represented here as pseudo code.

void operator()(T* p)

{

Mark Control Block invalid

Let passed in deleter do the deleting

}

At this stage, I have left it as pseudo code because how notify_ptrs should carry the passed in deleter D and the pointer to the control block is inconveniently conditioned by the requirements of transfer of ownership.

notify_ptrs should not impede transfer of ownership between notifying_unique_ptr and plain unique_ptr. Also in the case of transfer from notifying_unique_ptr to plain unique_ptr, it must zero any ptr_to_uniques referencing the owned object. This must be done because otherwise those ptr_to_uniques would be left with no notifications of deletion and could be left dangling.

We can get a smooth transfer from notifying_unique_ptr to plain unique_ptr simply by deriving notify_ptrs from the passed in deleter D. This will also give us Empty Base Class Optimisation and D is typically empty as in std::default_delete

struct notify_ptrs : public D

{

But this makes the transfer too smooth. It is so language elemental to take the base class of what is offered that there is nowhere to put code to intercept it and zero those ptr_to_uniques.

So instead notify_ptrs is not derived from D and a conversion operator is provided as the only path to achieve the transfer. And it is in this that we can put code to zero those ptr_to_uniques.

operator D& ()

{

Mark Control Block invalid

return passed in deleter D

}

The problem now is that if we hold the passed in deleter D as member then, even if empty, it will occupy storage just to have a distinct address from the pointer to the control block.

struct notify_ptrs

{

D deleter;

_ptr_to_unique_cbx cbx;

We have lost the Empty Base Class Optimisation that would have come from deriving from D rather than containing it. We want that Empty Base Class Optimisation back and we can have it with the following contrivance which defines how the passed in deleter D and the pointer to the control block are held.

struct notify_ptrs // if we derive from D, operator D& () will never be called

{

private:

//D will typically be dataless so we still need empty base class optimisation

struct InnerDeleter: public D

{

mutable _internal::_ptr_to_unique_cbx cbx;

};

InnerDeleter inner_deleter; // is a D

//provide a function to access the _ptr_to_unique_cbx cbx

inline _ptr_to_unique_cbx& get_cbx() const

{

return inner_deleter.cbx;

}

If we consider the case where D is empty as it is with std::default_delete;

struct InnerDeleter has just one data member, cbx, so its size is the size of cbx. There is no need for a separate address for D because InnerDeleter is a D.

We then give the notify_ptrs deleter just one data member, an InnerDeleter. This means notify_ptrs is the same size as inner_deleter which is the same size as cbx. We now have that Empty Base Class Optimisation for D.

The pointer to the control block is accessed using get_cbx() and inner_deleter is a D. So now, we can replace pseudo code with real code.

The deletion operator.

//The functor call to do the deletion

void operator()(T* p)

{

//zero ref_ptrs that reference this object

get_cbx().mark_invalid();

//leave deletion to passed in deleter

inner_deleter(p);

}

The conversion operator that allows and intercepts transfer from notifying_unique_ptr to unique_ptr

//Permits and intercepts move from notifying_unique_ptr to unique_ptr

operator D& ()

{ ///plain unique_ptr doesn't support ptr_to_unique

//so any that reference this object must be zeroed

get_cbx().mark_invalid();

return inner_deleter; //return the passed in deleter

}

We also need a conversion constructor to allow transfer from a plain unique_ptr to a notifying_unique_ptr:

//permit move from unique_ptr to notifying_unique_ptr

template< class D2,

class = std::enable_if_t<std::is_convertible<D2, D>::value>>

inline notify_ptrs(const D2& deleter)

{

}

ptr_to_unique

Like most smart pointers, the majority of the code consists of carefully composed conversion constructors and assignments. This is where most of the hard work is and determines its grammar of use. To keep the public interface clear, much of the work is delegated to commonly called private methods. In particular:

point_to(ptr) which is called by most constructors and assignments. If you look at its two versions, one taking ptr_to_unique and the other taking notifying_unique_ptr, you will see how the work is apportioned between the templated ptr_to_unique itself and the non-templated _ptr_to_unique_cbx cbx:

accept_move(ptr) which is called when the operand is falling out of scope. Knowing that the operand is going to die, there is no need to bump the reference count on the Control Block (slightly quicker).

checked_pointer() checks the control block before returning the raw pointer.

Some private aliasing constructors are also defined. They are currently not called and are there to support extended functionality which will be published in the near future.

In constructions and assignments, versions containing const&& arguments are defined to catch occasions when the source is falling out of scope.

Initialisation from a ptr_to_unique falling out of scope means move semantics can be used which can be more optimal.

Initialisation from a notifying_unique_ptr falling out of scope is prohibited so that you cannot write:

ptr_to_unique<T> puT = std::move(a_notifying_unique_ptr); //error - cannot take ownership

or:

ptr_to_unique<T> puT = std::make_unique<T>(); //error - cannot take ownership

Summary

The addition of ptr_to_unique 'upgrades' single ownership to match the pointer safety resources that have long been available for shared ownership. Single ownership is important and remains the correct and natural model for many designs. It deserves proper smart pointer coverage and ptr_to_unique completes this by acting as a safe refuge for its secondary references.

The table of available smart pointers can now be presented as follows:

| ownership | owning | non-owning | ||||

| single | unique_ptr<T> 0 overhead | don't *hold secondary refs. | ||||

notifying_unique_ptr<T> | <-- | ptr_to_unique<T> | ||||

| shared | shared_ptr<T> | <-- | weak_ptr<T> |

* hold – means to store and retrieve to use later.

You can continue to use the zero overhead unique_ptr<T> where you don't need to hold on to any secondary references but where you do, you can use notifying_unique_ptr<T> so you can hold those references safely with ptr_to_unique<T>. Shared ownership is already well supported by shared_ptr<T>/weak_ptr<T> and should be used when it is a correct expression of the design.

Why doesn't unique_ptr already have a smart weak companion like shared_ptr?

I found myself asking this question so I'm sure others will ask it to.

unique_ptr is zero overhead and that is important. It means that it can be used as a declarative owner everywhere including the most low level bare metal code without any fear of a downside. C++ has needed this ever since it provided the new and delete keywords. If new had returned a unique_ptr from the start we would have been saved a lot of trouble.

Anyway being zero overhead is not compatible with having a smart weak companion. So in its native state, unique_ptr simply can't do it.

With shared_ptr, zero overhead is a lost cause. It already supports reference counted control blocks so it was only a small extra price to hold the weak count required to support weak_ptr. That price had to be paid anyway because weak_ptr is a requirement for some of shared_ptrs most fundamental applications.

Now back to unique_ptr. It doesn't have built in support for weak smart pointers but it does give you the means to plug it in as an optional extra and this is exploited by ptr_to_unique.

So the real question is; Why did the Standard Library not provide that optional extra?

I think it is a matter of the Standard Library needing to carefully scope what it covers. It took on ownership and the smart pointers it provides do comprehensively cover that. The general safety of secondary references or pointers simply lies outside of that scope. They do things very properly and leave them well finished with no loose ends so widening the scope is a very big deal.

I did e-mail Bjarne Stroustrop some years ago about the perils of having no weak smart pointer to use with unique_ptr. He replied that he recognised the issue but it was unlikely that it would receive attention because it was all focused on updates to the language. There have been several updates to the language since then so my guess is that they left it there (ownership covered) and haven't got back to it (optional extras to help with pointer safety). Updates to the Standard Library often introduce components that could have been provided long ago if someone had got around to it.

It is fortunate that the authors of unique_ptr have, in true C++ tradition, provided a doorway for support for weak smart pointers to be customised in. It has to be an optional extra because there must always be a zero overhead unique_ptr.

History

- 21st November, 2021: First publication but many ideas derive from previous publications on The Code Project by the same author.

- 15th December, 2021:

Article title rephrased and Abstract rewritten.

Updates to source code in ptr_to_unique.h

ptr_to_uniquenow throws an immediate exception when calling the*operator on a null pointer

make_notifying_uniqueandcustom_make_uniquefunctions added.

Some background changes to facilitate extensions which will be published shortly.

New sections added to the article:

make_notifying_unique

Runtime error handling

Why doesn't unique_ptr already have a smart weak companion like shared_ptr?

Section on using your own custom deleter rewritten and repositioned.