Introduction

The purpose of this article is to show how to get progress notifications as data is sent and received from a web server during web service calls. This will be achieved by using a simple SOAP Extension.

I am using C# (2.0) in the article and in the attached solution. If there is demand for a VB.NET version, I'll provide one in the future. I have also stripped out some of the comments from the source code that appear inline in the article, to save some space and avoid saying a lot of things twice. Hopefully, the comments in the code are good enough so that you won't have to come back to the article for explanations once you've read it.

The following assumptions are made about the reader (i.e., I'm not going to explain these concepts):

- You know what a web service is.

- You know what a web service proxy is and how to create one in .NET.

- You are at least somewhat familiar with Interface based programming and delegates.

The following are the design goals of the proposed solution:

- Enable the caller of a web service method to receive notification as data is sent and received.

- Impose as little overhead as possible on the client developer.

- The solution should be self contained so that it can be re-used in any project that wants to implement web service progress notification.

- The solution must support multiple web service proxy classes pointing to different web services.

- No additional work is required if the client developer does not want to receive progress notification.

In order to receive notifications, we need to hook into the process of sending and receiving data as it goes over the wire. In the case of web services, this can be accomplished by a SOAP Extension. I will not provide a tutorial on SOAP Extensions, but I will try to explain issues that weren't obvious to me as I developed the progress notification solution.

The article is divided into two distinct pieces:

- A walk-through of the implementation and design.

- Step by step guide describing how to integrate the solution in your project.

You should be able to utilize the progress notification without going through the first part. However, should you decide to use it, I strongly urge you to familiarize yourself with the code before integrating the progress notification in your application.

The Progress Extension Project

As stated above, the progress notification project is implemented as a SOAP extension. There are two steps to implement a SOAP extension. One is to code the extension, and the second is to wire up the code with the .NET SOAP implementation. Let's start with the code. The project has three files.

- IWebServiceProxyExtension.cs

- ProgressEventArgs.cs

- ProgressExtension.cs

IWebServiceProxyExtension.cs

The IProxyProgressExtension is the interface that is to be implemented by the proxy class making the web service calls. When the .NET framework calls into the SOAP extension, you will see that we have access to the proxy class, more on that later. If the proxy class implements IProxyProgressExtension, we will query the proxy class for the information necessary to report progress.

namespace SoapExtensionLib

{

public delegate void ProgressDelegate(object sender,

ProgressEventArgs e);

public interface IProxyProgressExtension

{

string RequestGuid { get; set;}

long ResponseContentLength { get;}

ProgressDelegate Callback { get;}

}

}

ProgressEventArgs.cs

The ProgressEventArgs class is passed as the EventArgs in the progress callback.

namespace SoapExtensionLib

{

public enum ProgressState

{

Sending,

ServerProcessing,

Retrieving

}

public class ProgressEventArgs : EventArgs

{

private int m_processedSize;

private long m_totalSize;

private string m_guid;

private ProgressState m_state;

public ProgressEventArgs(int processedSize, long totalSize,

string guid, ProgressState status)

{

m_processedSize = processedSize;

m_totalSize = totalSize;

m_guid = guid;

m_state = status;

}

public int ProcessedSize

{

get { return m_processedSize; }

set { m_processedSize = value; }

}

public long TotalSize

{

get { return m_totalSize; }

set { m_totalSize = value; }

}

public string Guid

{

get { return m_guid; }

set { m_guid = value; }

}

public ProgressState State

{

get { return m_state; }

set { m_state = value; }

}

}

}

The above code should be pretty self explanatory, but there is one issue I would like to emphasize. Every web service call is conceptually a three stage process: send a request, let the server process the request, and receive a response. Let's say you want to retrieve a large amount of data from a web service. In this case, you might be interested in the progress while downloading the data, but not in the progress that is reported while sending the request. Another scenario could be to send a large file, have the server process that file, and retrieve the file back to the client. In this scenario, you might be interested in reporting all stages.

- Show progress while sending

- Display message: "Server processing…"

- Show progress while downloading the file

Our SOAP extension will set the progress status enumeration to one of the following values: Sending, Waiting, or Retrieving. The client can evaluate the progress status to decide whether to display progress or not.

ProgressExtension.cs

This is the main part of our progress notification project. The communication between a SOAP method call and a web server is implemented by .NET using the System.Net.WebRequest and System.Net.WebResponse classes. The writing and reading to the request/response stream of these classes is what actually drives the data over the wire. In order to report progress of the writing/reading, we need to somehow hook into the processing of these streams. Before we dive into the code, it is useful to understand the interaction between .NET and our SOAP Extension. When you inherit from the SoapExtension base class, there are several pure virtual methods that must be implemented.

public override object GetInitializer(Type serviceType)

public override object GetInitializer(LogicalMethodInfo

methodInfo, SoapExtensionAttribute attribute)

public override void Initialize(object initializer)

We don't use any of these in our SOAP Extension, so I will not go into details, but basically, the two GetInitializer methods are called once, and give you the option to set up any data that you might need later. Any data that was set up in these will be passed to you in the Initialize call. You can read up on these here.

After the initialization step, .NET calls our ChainStream method, giving us a chance to hook into the stream processing. In ChainStream, we will insert (chain) our stream into the reading/writing process done during a web service call. During a call to a web service, ChainStream is called twice. Once to chain the request stream for the outgoing request, and once for the response stream for the data returned from the web server. If you want to create a SOAP Extension that does not alter the data streams, there is no need to override the ChainStream method. (E.g., if you want to trace or log each web service call, you could do that without intercepting the actual data processing.)

Here is our implementation of ChainStream:

public override Stream ChainStream(Stream stream)

{

m_wireStream = stream;

m_applicationStream = new MemoryStream();

return m_applicationStream;

}

After the call to ChainStream, .NET will call into the heart of our SOAP Extension, ProcessMessage.

public override void ProcessMessage(SoapMessage message)

{

switch (message.Stage)

{

case SoapMessageStage.BeforeSerialize:

break;

case SoapMessageStage.AfterSerialize:

WriteToWire(message);

break;

case SoapMessageStage.BeforeDeserialize:

ReadFromWire(message);

break;

case SoapMessageStage.AfterDeserialize:

break;

default:

System.Diagnostics.Trace.Assert(false, "Unknown stage reported" +

" in ProgressExtension::ProcessMessage()");

break;

}

}

ProcessMessage is called four times during a web service call. During each call, you can evaluate the Stage property which indicates the current stage of serialization of the stream at the time ProcessMessage was called. The order of calls to ProcessMessage is BeforeSerialize, AfterSerialize, BeforeDeserialize and AfterDeserialize. The SoapMessage class passed to ProcessMessage has several properties, but note that not all of them are available at all stages.

You have to take into account that ProcessMessage is called both during sending the request and during receiving the response. Notice that while I named the methods WriteToWire and ReadFromWire to make the direction of the call explicit, we are not necessarily the last stream writing to the underlying sockets. There may be other streams chained through the same mechanism as we use to intercept the message processing. I decided it was better to be unambiguous in the naming to make the intent clear. Most samples I found online would name the streams newStream and oldStream. WriteToWire and ReadFromWire both set up whatever is needed for progress notification and do the actual stream processing.

Both WriteToWire and ReadFromWire get passed a SoapMessage argument. A SoapMessage can be either a client or server message depending on whether this SOAP Extension runs on the server or on the client. Since we are always running this on the client, we cast the message to a client message. Through the client message, we have access to the Client property which is the proxy class on which the call to the web service was made. This is the same proxy class that we previously extended with our IProxyProgressExtension. If the proxy class implements IProxyProgressExtension, we query the proxy for the size of the message and a callback that we use to report the progress. If your client project doesn't implement this interface, or has more than one web reference and you didn't implement this interface on all proxies, we just ignore progress notification for those that don't have the progress interface.

void WriteToWire(SoapMessage message)

{

SoapClientMessage clientMessage = message as SoapClientMessage;

m_state = ProgressState.Sending;

InitNotification(clientMessage);

m_applicationStream.Position = 0;

CopyStream(m_applicationStream, m_wireStream);

}

ReadFromWire is very similar to WriteToWire; only that we reset the stream to the beginning after we're done.

void ReadFromWire(SoapMessage message)

{

SoapClientMessage clientMessage = message as SoapClientMessage;

m_state = ProgressState.Retrieving;

InitNotification(clientMessage);

try

{

CopyStream(m_wireStream, m_applicationStream);

}

finally

{

m_applicationStream.Position = 0;

}

}

In order to be able to report progress, CopyStream reads from one stream and copies to another. If would read all the content of one stream and then copy it all to the other, we wouldn't have a way to report the progress. For that reason, we are processing the streams in chunks. The size of the chunks has some effect on performance, so you should benchmark your solution. A WAN about 8KB gave me a good balance between performance and steady progress notification. If you send very large amounts of data over lines of varying bandwidth, I would consider timing the transfer and setting the chunk size dynamically.

void CopyStream(Stream fromStream, Stream toStream)

{

int processedSize = 0;

byte[] buffer = new byte[ChunkSize];

while (true)

{

int bytesRead = fromStream.Read(buffer, 0, ChunkSize);

if (bytesRead == 0)

{

break;

}

toStream.Write(buffer, 0, bytesRead);

processedSize += bytesRead;

ReportProgress(processedSize);

}

}

If you look closely at InitNotification(), you will notice that setting the request GUID and callback delegates aren't necessary in the second call to InitNotification. (The second call is when we receive the response from the server.) This is because every call to a web service will trigger the instantiation of a new instance of our SOAP Extension. This instance lives throughout that call. I decided that I preferred to have a single method with some insignificant overhead than two different methods, since the overhead is so low.

void InitNotification(SoapClientMessage clientMessage)

{

if (clientMessage.Client is IProxyProgressExtension)

{

IProxyProgressExtension proxy =

clientMessage.Client as IProxyProgressExtension;

m_requestGuid = proxy.RequestGuid;

GetContentLength(clientMessage, proxy);

m_progressCallback = proxy.Callback;

}

}

In order to allow the caller to calculate how much we have processed, we need to know how much data we are going to send or receive. If we are receiving data from the web server, the WebResponse class has a property for the ContentLength that we can access to get the number of bytes the server is going to send us. When we are sending data, the size of our stream is the amount of data to be sent.

void GetContentLength(SoapClientMessage clientMessage,

IProxyProgressExtension proxy)

{

if (clientMessage.Stage == SoapMessageStage.BeforeDeserialize)

{

m_totalSize = proxy.ResponseContentLength;

}

else if (clientMessage.Stage == SoapMessageStage.AfterSerialize)

{

m_totalSize = clientMessage.Stream.Length;

}

else

{

m_totalSize = TotalSizeUnknown;

}

}

The only thing left is to report the progress back to the caller if we have a reference to the callback method.

void ReportProgress(int processedSize)

{

if (m_progressCallback != null)

{

ProgressEventArgs args = new ProgressEventArgs(processedSize,

m_totalSize, m_requestGuid, m_state);

m_progressCallback.Invoke(this, args);

}

}

The output of this project is a SOAP Extension assembly that can be reused in any project that accesses web services. One issue remains though. How do we tell .NET to use our SOAP Extension? There are two options. One is to use attributes, and the other is to use a configuration file. One of the goals of this project was to provide an easy path for the client developer in integrating progress notification. For that reason, I chose to use app.config to tell .NET to use our SOAP Extension. If you, for some reason, wanted only some web service calls to use your extension, you should use attributes. They allow you to specify on a method-by-method basis which methods should be processed by the extension. Using the configuration file will cause all web service calls to be processed by the SOAP Extension.

Sample configuration file:

="1.0"="utf-8"

<configuration>

<system.web>

<webServices>

<soapExtensionTypes> <add

type="SoapExtensionLib.ProgressExtension, SoapExtensionLib"

priority="1" group="High" />

</soapExtensionTypes>

</webServices>

</system.web>

</configuration>

The section related to SOAP Extensions is <system.web>. In the <add> element, the first part is the type, and the second is the name of the assembly that contains the extension. If you have more than one SOAP Extension, you can control the order they are chained together by setting the priority and group values. The group can be either high or low, and the priority is from 1 to 9. When .NET chains all present SOAP Extensions, they are first sorted by group and then by priority. You get High 1-9 and then Low 1-9.

Receiving Progress Notification

A project with a web reference to a web service contains a proxy class that implements the low level (at least, reasonably low level) SOAP HTTP protocol. This proxy class implementation uses one of the new features introduced in .NET 2.0, Partial Classes. In step two below, we will use this feature as an extensibility mechanism that separates the generated code from the application code.

Detailed steps (all the steps are shown in code as well):

- Add a reference to the SoapExtensionLib.dll assembly in the project that contains the web reference.

- Add a new class to the project. The name of this class needs to be the same as the proxy class created by Visual Studio, with the addition of the

partial keyword in front of the class declaration. The class must also reside in the same namespace as the proxy class. To get the namespace, open the Reference.vb/cs file in the "Web References" folder and copy the namespace declaration from there. - Implement the interface

IProxyProgressExtension on your partial implementation of the proxy. - Hook up the progress delegate to the proxy class before calling a web method.

In step three, we implemented the interface IProxyProgressExtension. The implementation is independent of a specific proxy class, and an immediate question is: couldn't this be implemented as a base class instead? That would be a better solution IMHO, but the problem is that the proxy class already has a base class in the generated code. The generated class declaration in the proxy inherits from System.Web.Services.Protocols.SoapHttpClientProtocol, and we can't inherit from another class. However, there is no limit to how many interfaces we can implement.

Sample Progress Extension Class

using SoapExtensionLib;

using System.Net;

namespace TestClient.localhost

{

public partial class Service : IProxyProgressExtension

{

private WebResponse m_response;

private string m_requestGuid;

public ProgressDelegate progressDelegate;

protected override WebResponse GetWebResponse(WebRequest request)

{

m_response = base.GetWebResponse(request);

return m_response;

}

#region IProxyExtension Members

public string RequestGuid

{

get { return m_requestGuid; }

set { m_requestGuid = value;}

}

public long ResponseContentLength

{

get { return m_response.ContentLength; }

}

public ProgressDelegate Callback

{

get { return progressDelegate; }

}

#endregion

}

}

Sample Web Service Call

private void callWebServicebutton_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

localhost.Service proxy = new TestClient.localhost.Service();

proxy.progressDelegate += ProgressUpdate;

string result = proxy.ProcessXml(GetLargeFile());

webServiceProgressBar.Value = 0;

statusLabel.Text = "";

MessageBox.Show("Done");

}

Sample Progress Display

void ProgressUpdate(object sender, ProgressEventArgs e)

{

double progress = ((double)e.ProcessedSize / (double)e.TotalSize) * 100.00;

webServiceProgressBar.Value = (int)progress;

statusLabel.Text = e.State.ToString();

this.Refresh();

}

Running the Sample Project

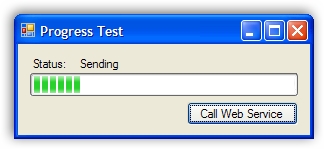

The included sample code contains the SoapExtensionLib project, a sample web service (using Casini), and a test client. When you press the "Call Web Service" button, you will be prompted to choose a file from the file system. This file will be serialized to base64 and sent to the web service. The web service will just return whatever it receives.

Conclusion

That concludes our journey on reporting progress from a web service call. If you have comments and/or questions, please leave a comment, or contact me through my blog.

References: